Let’s face it: after years of exposure, our brains have been trained to mindlessly scroll along when running into the topic. That’s understandable, but no excuse. Like other typical examples such as greenhouse gas emissions and the mass extinction of animal species, most of us have known about the problem of plastic pollution for a while. Yet, we dismiss it as ‘not being ours to solve’ on a personal scale, while we can’t seem to even make a dent in the problem on a global level. To what extent is the latter true, and what can be done to tackle the downsides of this magnificent invention?

Currently, the way our society uses plastics is inefficient and toxic to the environment. Since their introduction more than a century ago, most plastic has been single-use: after unwrapping your protein bar, the wrapper is discarded in the bin, the contents of which are often not (completely) recycled. We have come a long way with re-using glass, but plastic collection bags have only started popping up in recent years.

Additionally, a lot of plastic suffers another fate: when the bin is full, when a government lacks financial motivation for recycling, or simply when some people feel lazy, the wrapper ends up in nature. It might sound far-fetched, but bits of this wrapper may end up going fullcircle and become part of your diet as well.

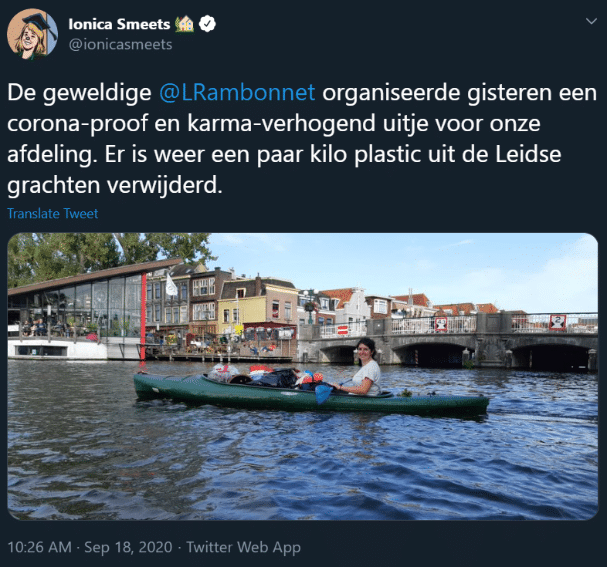

As can be expected, this one wrapper is not alone. In Leiden, the fish that live in the 28 kilometers of waterways within the city haven’t been alone for a long time. Plastic cups and bottles are now most of the biodiversity and plastic straws have proven to be valuable building blocks for ducks’ nests.

Numerous stories exist of animals suffering as a result: turtles getting the plastic rings often used for canned 6-packs in the U.S.A. stuck around their neck resulting in life-long growth deformities, turtles mistaking plastic bags for edible jellyfish, and even a sperm whale that washed ashore in Spain after eating 29 kilos of plastics – and dying due to blocked digestion as a result.

Of course, on a bigger scale, bigger problems exist. Leiden’s 28 kilometers are not a closed circuit; the Rhine river carries all this waste to the North Sea. From there, it joins other streams of plastic and accumulates in one of the ocean’s plastic ‘hotspots’. Due to the ocean’s currents, these hotspots are traps from which the plastic can’t escape. About 79 thousand tonnes of plastic reside here, while the ‘pile’ grows every day. To put it another way: the weight of 60.000 average-sized cars.

It is important to make the distinction between different sizes of plastic. When comparing total weight of the types, the vast majority of this ‘Great Pacific garbage patch’ consists of bits of plastic that are easily visible. When comparing particle numbers, most of the Patch consists of so-called ‘microplastics’.

Microplastics are where the full circle comes in. Since these particles are sometimes microscopically small, they have made their way into the diet of even more marine animals, traveling up the food chain. A study found that virtually all people six years or older now have traceable amounts of BPA in urine samples. Microplastics are not unique to fish; scientists in Minnesota conducted a survey of tap water and found particles in about 4 out of every 5 samples. It has been estimated that the average person eats about a credit card’s worth of plastic every week.

Luckily, efforts to tackle this question have been popping op on both small- and large-scale. In Leiden, the municipality has joined forces with the university to establish “Plastic Spotter”, a project that involves citizens by cleaning up city canals using canoos and an app called CrowdWater that citizens can use to report plastic waste, helping researchers to find possible patterns in the locations of waste, hoping to aid the city to limit the process as much as possible.

Now, bigger problems require bigger solutions, but big ships are unable to catch microplastics. To circumvent this hurdle, Boyan Slat founded The Ocean Cleanup, aiming to develop passive capturing systems to efficiently collect ocean garbage while avoiding by-catch. Recent developments in the project show that they are able to retain microplastics and can filter thousands of kilos from the ocean. The project has recently expanded into the field of rivers as well. The newest development, called The Interceptor, sits in rivers and can collect 50.000 kilos of trash per day.

Finally, we must consider our own role in the plastic industry. Solutions to the symptoms do help, but the cause of the problem must be taken away to completely solve it. Luckily, each day more efforts are visible to re-use and recycle plastic while limiting their spread into nature as much as possible, such as plastic collection days and deposits on smaller bottles coming soon.

The cleanup of oceans seems to be picking up pace. As a beginning, both small and big cleanup efforts help on the short term. Ultimately, a combination of cleanup and changing our behaviour with plastic will be necessary to preserve ocean life and protect ourselves from having ‘plastic soup’ served for lunch.

Comments